The Most Powerful Computer

The most powerful computer you have working for you in your organization is the human mind. Human beings are able to intuit things that they cannot explain, define or even fully comprehend, and yet act accurately and effectively in response to this intuition.

Consider, for example, a young baseball player. He (or she) can hear the crack of the bat and the smallest of visual clues from the angle at which the ball leaves the bat and immediately begin moving toward the proper location to intersect with the arc of the ball through the sky. Then, having arrived at the right speed to the right spot, place the glove in the path of the ball and intercept its fall to the ground.

Now, most of those baseball players could not tell you the mathematical formula that would predict the location at which the ball would fall, with all its vectors and forces. Nevertheless, their minds are able to intuitively know and understand how, when and at what speed they need to react to achieve the goal of the team.

The same is true of the minds at work in your enterprise. Given the opportunity, when your employees see that their input is valued in a process of ongoing improvement (POOGI), their minds become powerful forces for innovation, improvement and growth.

Complexity Slows Us Down

By contrast, to intuition, complexity slows us down. Complexity has this effect because it limits our ability to use the power of our intuition.

Unfortunately, sometimes our attempts to "simplify" our business and our organizations actually add to the complexity and slow the flow of the work.

In our misguided attempts to "simplify" and better "understand" our organizations and processes, we frequently try to break them down in smaller units of work and function. We create departments and functions in the hope that we can better grasp the requirements and capabilities of each individual department or function.

Sadly, this actually results in added work and added complexity as, having broken the process flow down into smaller units, we must now create some method to keep these smaller functional units synchronized.

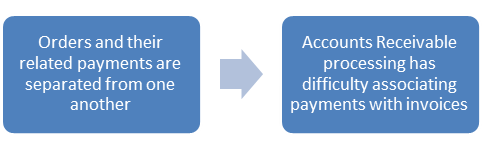

At our clients, we usually see this effect at work in several ways. A good example at one client was the fact that, they had separated the "prepayment" process from the "order entry" process. As a result, they found it necessary then to create a special report and complex email messages to re-synchronize the payments with the resulting invoices.

When we artificially break the flow of the whole system into functions and segments, then management tends to try to "fix problems" in isolation.

Going back to our example, rather than looking at the whole system flow—from order-to-cash—once the system was segmented, the report was "the fix" developed to reconnect the data from one isolated process to a subsequent isolated process.

The Fear

Sometimes "problems" are dealt with in isolation out of an underlying fear that, if we get the whole organization together so that we can drive to the root of this problem, it may lead to conflict and finger pointing. Besides, if we resolve the issue locally—within a single department or function—it becomes easier for us demand accountability.

Symptoms and Undesirable Effects

Sadly, when we deal with what we believe are "problems" and we deal with them in isolation—within a functional silo and without consideration of the entire system flow—we are most often dealing with symptoms and not the core problem.

Consider this cause-and-effect:

Wrong assumptions made in one function actually was the cause of the issue arising in the next function in the chain of events.

In our example above, accounts receivable was not really experiencing "a problem"—although that is likely how management viewed it. The accounts receivable function was experiencing "an undesirable effect" or "UDE," as we call them, stemming from something else being done (or, rather, not done) in another part of the system.

We call such results "UDEs" (rhymes with "cooties") to avoid calling them "problems."

If it is "a problem" we want to fix the problem. If it is a UDE, we want to find the root cause of the problem.

And, once we have uncovered the root cause of the UDE, we want to apply INHERENT SIMPLICITY to uncover the simplest possible solution that will permanently resolve the root cause.

We want to deal with "the disease" and not the symptoms of the disease.

Two Fundamental Principles

This concept of understanding "root causes" and looking at your system holistically—from product design all the way through to booking the profits—is a principle joining two distinct elements: system thinking and inherent simplicity.

System thinking means never trying to solve "problems" in isolation—without understanding the root causes

Inherent simplicity means that, the more complex the problem appears to be, the simpler the effective solution must be

When we work with clients on business process and supply chain issues, we are constantly helping them drive back to these two elements of sound management.

Sophistication Leads to Management Errors

Management generally tries to…

- Force certainty on uncertainty

- Force compromise on conflict

- Force simplicity on complexity

We have already discussed number three: Management tries to force simplicity on complexity by attempting to break down complexity into manageable chunks, and then managing each chunk separately. In doing so, they lose sight of the system as a whole. They can no longer see the (whole) forest because the (individual) trees are too prominent in their thinking. "Specialization" of functions obscures the real complexity that managers must address to achieve breakthrough results in their business and in their industry.

Here is another example where specialization keeps management from seeing their system holistically: sales management teams (in their specialization) sometime spend months or years honing a "just right" end-of-season discount policy to deal with overstocks. Because of their specialization, however, they never seem to consider trying to find a way to prevent overstocking in the first place.

Management frequently assumes that we need ever-greater sophistication and complexity to achieve its goals. We find, repeatedly, however, that the most effective breakthroughs stem from the firm's ability to challenge successfully the fundamental underlying assumptions in their organizations, in their supply chains, and in their industries as a whole.

Sophistication carries with it the promise of certainty, but in never delivers on that promise.

Management Attention is Your Most Precious Resource

Not money, machines, or technology limit most organizations. Even their market is not the critical limiting factor. The limiting factor is management's ability to direct actions that will effectively achieve more of their goals.

We, here at RKL eSolutions, believe that the most effective approach to dealing with the threefold business challenges of uncertainty, complexity, and conflict is to recognize them and include them in your firm's overall business strategy.

Splitting management's attention between our goals and separate efforts to deal with uncertainty, complexity, and conflict will lead to mediocre results. We believe the most successful organizations employ tools and develop processes that help them achieve their goals while creating an evolving reality in which these three challenges are either removed or reduced to a manageable level through sound strategies and tactics.

Focusing on Exceptional Customer Value

Companies like Toyota, Apple, and many others have shown that developing a business strategy focused on delivering exceptional value to customers is key. When a holistic view is taken of the organization and its supply chain with the singular focus being "exceptional customer value," something exciting begins to happen that can take an average company and turn it into a market-dominating leader.

This is our hope for you.