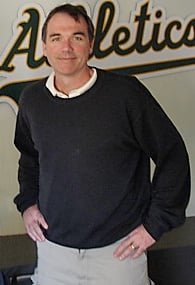

Recently I went back to watch “Moneyball” again. The 2011 film is based on the real life story of Oakland A’s general manager Billy Beane and a statistician by the name of Paul DePodesta. These two men changed the game of baseball by changing how the game (specifically, “the team”) is viewed by managers and executives.

“It’s unbelievable how much you don’t know about the game you’ve been playing all your life.” – Mickey Mantle

Without retelling the entire story, allow me to summarize.

Beane said, “It’s an unfair game.” He recognized the real state of affairs. In the film, Beane went on: “There are rich teams and there are poor teams; then there’s 50 feet of crap; and then then there’s us.”

But he didn’t say this with resignation. Instead, he told his staff and managers: “We’ve got to think differently…. If we try to play like the Yankees in [the back office], then we will lose to the Yankees out there [on the playing field].”

Start by thinking differently

Billy Beane started by thinking differently—but he didn’t yet know how he ought to think. He just knew that conventional wisdom was never going to let his team have any hope of making any real gains against industry leaders and “giants.”

He refused to let his managers and executives continue “business as usual,” where they seemed to think that fighting fires and restoring normality (i.e., “how it was before”) could be a substitute for real improvement.

On a recruiting visit to another team’s offices, he stumbled upon what he believed was to be the key to unlocking a way for his team to gain an advantage against his league-leading rivals. Beane met up with Paul DePodesta (Peter Brand, in the film), a statistician doing “player analysis” for a competitor.

Here’s what Peter Brand (aka Paul DePodesta) told Beane in the film:

There is an epidemic failure within the game to understand what is really happening, and this leads people on major league baseball teams to misjudge their players and mismanage their teams….

People who run ball clubs… think in terms of buying ‘players.’ Your goal shouldn’t be about ‘players;’ your goal should be about ‘wins.’ And, in order to buy ‘wins,’ you need to buy ‘runs.’

… When I see [what other folks call ‘a star player’], I see an imperfect understanding about where runs come from….

Baseball thinking is medieval. They are asking all the wrong questions. And, if I say it to anybody, I’m ostracized….

Misapplication of both intuition and statistics

“Moneyball” provides a great and very applicable metaphor for studying the misapplication of both intuition and statistics for ongoing improvement. You’ll have to watch the movie (again, perhaps) to catch more of it. I did.

The “old way” of baseball recruiting was to use scouting “intuition” (about everything from the player’s appearance to the kind of girlfriend they had) in conjunction with some statistics about past performance in crude attempt to prognosticate about the player’s future performance. As right or wrong the decisions may have been about forecasting the future performance of the individual players, it was entirely focused on local optimization—that is, trying to select each player and improve each player. The underlying assumption was that local optimization would lead to improvement of the system as a whole.

What Beane and DePodesta brought into clear relief was that focusing on the entire “system”—buying ‘wins’, or playing ‘moneyball’—would allow better performance at lower cost.

Better performance at lower cost—isn’t that the “holy grail” of every for-profit business enterprise? What need we learn?

Lots of parallels

There are several business parallels that can be drawn from the concepts proven by Billy Beane, Paul DePodesta and the Oakland A’s in their 2002 season. Here are a few:

-

Lean/Agile Development – Breakthrough thinking in the world of Lean or Agile software development has helped changed management’s understanding about how to direct the work of a group of what used to be called ‘prima donnas’. It is no longer about ‘buying players,’ but it is all about ‘buying wins’ and creating a that fosters ‘wins’—and profits—through improved productivity.

-

Lean/Agile Supply Chains – New concepts about supply chain management are chaining the view of managers and executives about the ‘key supplier’ and the premiums sometimes paid to keep them happy in the supply chain.

-

Theory of Constraints – Stop optimizing “departments” and “functions” and start optimizing the whole system (system thinking). Start grooming the entire system for “wins,” and stop grooming the individual “players.”

Peter Brand, the Yale-educated economist who was doing player analysis in the film, told Billy Beane: “From among the 21,000 prospects we can evaluate, I believe we can find a winning team of 25 players who are undervalued and that we can afford.”

I believe the same is true in a supply chain, for example. I think there are dozens—even hundreds—of supply chain ‘players’ out there who are presently ‘undervalued’ by their industry and could become part of a winning, collaborative supply chain ‘team.’

What lesson can we take from this?

Even when the playing field seems utterly “unfair” and you are competing against giants in your league, if you look to system thinking instead of local optimization, your chances of winning are dramatically improved.

We would like to hear what you think. Please leave a comment here, or contact us directly.