If your company and supply chain is like most companies and supply chains, you are doing everything you know to try to reach more of your goal—trying to make more money tomorrow than you are making today. You are trying diligently to improve your return on investment (ROI).

So, why is it—with all the programs you've tried, all the talent you have onboard, all the experience your company has on staff, and with all the big investments you've made in time, energy and money—that real, long-lasting bottom-line improvements are so elusive?

Don't Feel Lonely

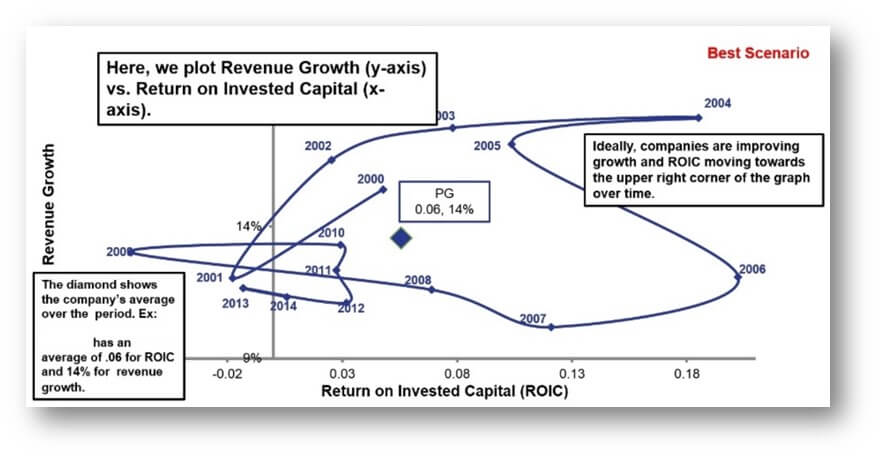

The accompanying graph represent data from a Fortune 500 company you would know if I could name it here. They spend millions on their supply chain efforts, and have for many years. (Graphic adapted from Cecere, Lora, and Regina Denman. Supply Chains to Admire - 2015. Report. September 8, 2015. Accessed December 3, 2015. http://supplychaininsightsglobalsummit.com/supply-chains-to-admire/.)

Nevertheless, when plotting revenue growth against ROIC (return on invested capital) for this company, we see the firm not in a pattern of ongoing improvement, but quite literally, wandering all over the place.

ROIC for the firm was negative in three years between 2000 and 2014 (2001, 2009 and 2013). The only brief period which could logically be described as a period of ongoing improvement was the years 2001 through 2004—when their trend was upward and to the right on the graph, indicating growth in revenues and improving ROIC.

After that, however, the magic vanished somehow. Between 2006 and 2009, even though revenue growth was relatively steady, return on investment was steadily declining—and has no yet recovered!

Aligning Resources to Strategies

I don't know about you, but I am guessing that the executives at this firm did not decide in after 2004 to switch strategies and work in the direction of lower revenues and declining ROI!

No!

Executives virtually always set forth strategies for improvement. But, the ability to effectively implement the strategy for improvement means being able to tactically align internal and supply chain resources so that they act in a coordinated way to improve and reach the desired strategic goal.

Resource Contention

If the executive team and managers at every level do not fully understand the interdependencies between the various participants, functions and silos of operation across the company or the extended supply chain, then it is inevitable that resource contention will arise between initiatives, programs, and investment decisions (and the metrics that drive them). In most companies—like your own, and the one we see in the accompanying graph—improvements in one area are (unintentionally) offset by unintended consequences in another area of the business or supply chain.

This is exactly what happens when improvement programs and decisions are made at the local level—instead of being made with a system-wide view of the enterprise or supply chain.

You have probably been through this cycle many, many times already: In order to reduce inventories, we end up causing stock-outs and manufacturing delays. In order to trim away at costs, we hurt our quality or damage our ability to deliver to our customers on time. So that we can get one project completed or product delivered on-time, we expedite it and, in doing so, end up causing other projects or products to be delivered late or needlessly delayed.

Sadly, we invest more and more in accounting systems, new metrics, and financial incentives focused on improving the performance of local function after local function, silo after silo, only to find that these local improvements have no positive effect on our bottom-line—at least, not for long. And, worse, the local improvements actual trigger something else—something we may not even be able to clearly identify—and our bottom-line gets worse after the "improvement."

An Organization in Conflict with Itself

As Debra Smith put it so very well:

Agreement on the need for a measurement system that encourages local actions in line with a company's bottom-line results is common, but it continues to be elusive. Traditional cost-accounting product cost allocation, using direct labor to assign overhead to the products with a focus on local labor and machine efficiencies, is at best irrelevant and at worst dysfunctional.... An organization in conflict with itself by definition is not aligned and cannot execute even the best strategy to its highest potential. (Smith, Debra. The Measurement Nightmare - How the Theory of Constraints Can Resolve Conflicting Strategies, Policies, and Measures. Boca Raton, FL: St. Lucie Press, 2000.)

Enterprises and supply chains—clearly, even at Fortune 500 companies—remain bound in their internal conflicts mostly because most of the classic schools of business in our nation teach their students to manage complexity by breaking it down in manageable chunks. We call those chunks divisions, departments, functions—silos of every description. In doing so executives and managers lose sight of the big picture—that the companies and supply chains do not operate as silos, they operate as a chain of dependent events and actions.

Most executives and managers today have not been provided with the tools to clearly be able to lay hold of a system view of their enterprise or supply chain. Again, Debra Smith helps state the need so clearly:

Without comprehensive education of mid-management and the ability to clearly diagram the conflict, middle management and first-line supervisors are hopelessly forced into action that usually compromises at least one of the objectives. If they are being measured with multiple competing objectives, they objectives. If they are being measured with multiple competing objectives, they all of the competing measures so it is impossible for the plant to win. It is still possible for the person in charge of only one program to "win" but often everyone else and the company loses. (Smith, ibid. p. 18)

We freely confess, as consultants to enterprises and supply chains, we do not have all the answers. But, we can bring the tools and education to managers and executives so that they can, first of all, understand how and why they companies work—and fail to work—and then move on effectively to creating their own solutions to their unique circumstances.

Helping achieve a system view and bring an end to internal conflicts can get companies on the road to real and enduring ongoing improvement.

How is your company or supply chain doing? Are you seeing lasting improvement, or are you wandering like the Fortune 500 company in the graph above?

Let us know. We would be delighted to hear from you.