Supply Chain in Flux

We like the term "supply chain." And, it probably isn't going away anytime soon.

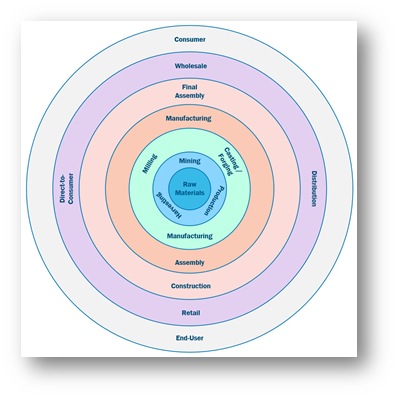

The term is convenient, even though "chains" have evolved into "networks," and, more recently, there is a growing realization that the "levers" that we used to think would help us control our supply chains just aren't working.

We like the term "chain," I think, because it reminds us that goods and services flow from source to consumer in a series of dependent events. But we are increasingly aware that the concept of a "chain" simply does not adequately describe what actually transpires.

The biggest body of evidence that we have that our supply chain isn't a "chain" can be found in our ready admission that everything in our supply chain is in a constant state of flux. We have grown to recognize that our supply chain needs to have built-in agility, flexibility, and resilience to really support FLOW.

Complex Adaptive Systems

It is not even sufficient merely to refer to our former "supply chains" as "networks" or "systems." They are networks and systems, but they are more than that, as well.

Scientists have come up with a term to describe what our supply chains really are: complex adaptive systems or CAS, for short.

So, what is a CAS?

A complex adaptive system consists of many diverse and autonomous components or parts (called agents) which are interrelated, interdependent, linked through many (dense) interconnections, and behave as a unified whole in learning from experience and in adjusting (not just reacting) to changes in the environment…. Each agent maintains itself in an environment which it creates through its interactions with other agents. [1]

As executives and managers, we like to—well, you know—manage.

But here's the thing about CAS:

Every CAS is more than the sum of its constituting agents, and its behavior and properties cannot be predicted from the behaviors and properties of the agents. CAS are characterized by diffused (distributed) and not centralized control and, unlike rigid (mechanistic) systems, they change in response to the feedback received from their environment to survive and thrive in new situations. In the inanimate world, many phenomenon behave as CAS, such as fashion trends, stock markets, traffic jams. [2] [Emphasis added.]

On the positive side, a CAS is greater than the sum of its parts. In business, some economists and management theorists refer to this as the X-factor (the inverse of x-efficiency). [3] It is that unidentifiable element that means that one firm may succeed (or dominate) and another fail (or be mediocre), even though both have essentially the same resources and skills available to them.

Also, on the positive side, each agent (say, supplier or customer, in a supply chain context) can respond independently to inputs from its environment in order to survive or thrive. That means, as a supply chain executive or manager, you don't have to take responsibility for the survival of trading partners. (That doesn't mean you don't have an interest in their survival. It only means you are not responsible for their survival.)

You get what you measure

There is an old management axiom that reminds us that management "gets what it measures." This old saw was intended to be a positive reminder—and, it is.

But what too many executives and managers fail to consider is measuring what they really want to get.

Consider the recent debacle at Wells Fargo Bank. Well Fargo's executives decided to measure employee performance-based the number of new customer accounts that were opened. And, what did they get? Lots of new—mostly fake—customer accounts opened. It cost them millions of dollars and a good deal of their reputation.

What did Wells Fargo executives actually want? They wanted more customers and more accounts. They wanted to grow their business.

But, their employees were not machines. They were agents acting independently in a complex adaptive system. They adapted to the inputs from their management environment and did what achieved the best outcomes for themselves—read: they didn't get fired and/or they received bonuses.

Learn to appreciate the difference

Your supply chain is not a chain. It is a complex adaptive system.

If your supply chain is going to survive and thrive in the coming years, you will probably need to learn to manage it with an entirely different set of tools—and different thoughtware, most likely.

Unfortunately, most executives and managers today do not really comprehend the difference and are still trying to manage using machine thinking. [4] They are still trying to understand their supply chain by breaking it into pieces, managing each piece, and assuming that their supply chain is the sum of the pieces. It is not.

We, here at RKL eSolutions, are intent on helping companies get a new view of their supply chains. We help executive and management teams acquire and install new thoughtware—that is, new ways of seeing and managing.

The new demand-driven approach we bring is fully aligned with the CAS theory of supply chains. The DDMRP approach has proven to be not only easier to implement and smoother in operation, but also more efficient at providing rapid return on investment than traditional planning and execution approaches.

How are you learning to manage your supply chain as a CAS?

What have you done to move off traditional approaches and onto new, more effective means for seeing and managing what is happening?

Please tell us by leaving your comments below, or by contacting us directly, if you prefer. We look forward to hearing from you.

****************************************

[1] "What Is Complex Adaptive System (CAS)? Definition and Meaning." BusinessDictionary.com. Accessed January 16, 2017.

[2] BusinessDictionary.com, ibid

[3] [M]otivational advantage will often decide the success or failure of enterprises... otherwise equally endowed. Harry Leibenstein of Harvard has presented a large body of evidence which shows that the key factor in productivity differences among firms... is neither the kind of allocational efficiency stressed in economic texts nor any other measurable input in the productive process. The differences derive from management, motivation, and spirit; from a factor he cannot exactly identify but which he calls X-efficiency.

Gilder, George F. Wealth and Poverty. New York: Basic, 1981. Print.

[4] Franz, James K., and Jeffrey K. Liker. "The Toyota Way: Helping Other Help Themselves." www.sme.org. November 2012. Accessed September 9, 2013. http://www.sme.org/MEMagazine/Article.aspx?id=69059&taxid=1415.

****************************************