For most of the time since the late-1980s, the market capitalization for Toyota roughly equaled, or exceeded, the sum of the "Big Three" in Detroit. Although wishful thinkers today attribute much of Toyota's present profitability to currency manipulation of the Japanese yen, in the 1990s, with a depressed yen and an exploding U.S. stock market, Toyota's market value still exceeded that of its much larger competitors. [1]

"The ability to focus on long-term objectives has been a critical factor in success at Toyota," say James Franz and Jeffrey Liker writing on the SME (Society of Manufacturing Engineers) website. [2] This long-term thinking Franz and Liker set in apposition to the typical thinking they find in most other companies. The writers continue: "Contrast this to the 'typical' thinking that we encounter in other companies. We find that most publically-traded companies are intently focused on the next quarter's numbers…." The results of such thinking tend to lead to actions resulting in "superficial improvements that cannot be sustained over any period of time." [3]

Let's not pretend

Okay. Let's not pretend that this focus on the short-term outcomes is a symptom found only in publically-traded companies.

We work almost entirely with privately-held companies and find that they, too, are very frequently afflicted with the same short-sightedness.

Granted. The short-term thinking in publicly-traded corporations is mostly driven by the need to show some kind of improvement in the next quarterly report—and by C-suite bonuses frequently driven by such results. Whereas, the short-term thinking in most privately-held companies is driven mostly by other factors—like cash flow, reports to lenders, such.

Nevertheless, the short-sightedness persists.

And the persistent short-sightedness drives many actions that are damaging to the long-term prospects and competitiveness of the companies.

I remember the 1980s well

I well remember the 1980s. U.S. automakers were struggling against imports from Germany, Japan and elsewhere.

While U.S. automakers reported quarter after quarter of (frequently) record-setting losses—losses in the billions of dollars—they were unanimously intent on one thing: cost-cutting.

Yet, the more they cut costs, the more their profits declined. Meanwhile…

Toyota, too, was very focused. Toyota was focused on the one thing that they knew would make them profitable in the long-term: that one thing was FLOW.

Oh! The irony of it all

Yes. The U.S. "Big Three" were focused on cost-cutting—reducing costs through ever-improved efficiencies. And, Toyota was focused on FLOW.

But, here is the real irony of it all.

To appreciate the starkly different kinds of thinking that characterize Toyota and the American Big Three [automakers], consider the following meeting in 1982 between Eiji Toyoda, then head of Toyota Motor Corporation, and Philip Caldwell, then head of the Ford Motor Company. At the time, Toyota was emerging as the lowest-cost producer of the highest quality automobiles in the world. Ford and its Big Three partners were then plagued by falling market share, rising customer dissatisfaction with the quality of their vehicles, and unprecedented financial losses. Presumably, Caldwell visited Toyota in Japan in 1982 seeking new ideas. During Caldwell's visit, his host, Mr. Toyoda, is said to have toasted Mr. Caldwell by saying, "There is no secret to how we learned to do what we do, Mr. Caldwell. We learned it at the Rouge." [4]

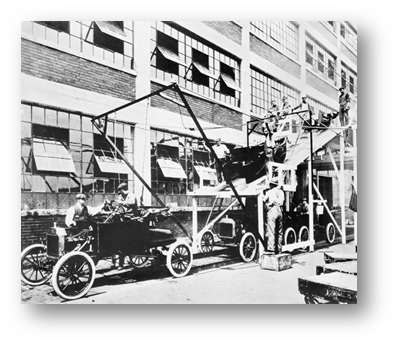

The "Rouge" referenced by Mr. Toyoda was Henry Ford's River Rouge complex near Dearborn, Michigan, which both Kaiichi Toyoda and Eiji Toyoda visited. Kaiichi visited 'the Rouge' in 1929 and his nephew, Eiji Toyoda, visited it again in 1950, to study Henry Ford's methods.

And, what was Henry Ford's adamant focus and, indeed, the underlying concept behind the River Rouge complex's design and development?

The answer is simply this: FLOW

Not costs, but FLOW.

Henry Ford understood that if you had FLOW—if you focused on FLOW; if you maintained FLOW—that efficiencies would automatically be high and costs would automatically be low.

Somehow, all that got lost by Ford and other U.S. automakers as they focused more and more on short-term outcomes.

Think about that next time

Think about that next time you—or someone else in your company's supply chain—says something like:

"We've got too much inventory! Cut it."

"Why are we out of stock on that? Everyone knows it's critical."

These kinds of statements clearly show that FLOW has been disrupted. Overstocks mean FLOW has unexpectedly slowed or stopped. Out-of-stocks indicate that FLOW on the supply side has slowed or stopped, or that FLOW on the demand side has unexpectedly increased.

Worse!

The commands just offered don't touch at all on the long-term health of the organization. They are just short-term, firefighting orders intent on restoring normality—even if "normal" was way below optimal.

Just think about it.

Are you focused on FLOW and the long-term health of your supply chain? Or are you merely trying to get through the end of the day, the end of the week, or the end of the month.

Is there any linkage at all between your day-to-day actions and your supply chain's long-term strategy? Do you even have a long term supply chain strategy?

We can help.

How you are addressing these kinds of challenges in your supply chain? Do you have a process of on-going improvement (POOGI) in place?

Learn More - Whitepaper - Why Your Supply Chain Needs a 'POOGI'

Click below to grab your complimentary copy of the whitepaper!

Whitepaper

[1] Johnson, H. Thomas, and Anders Bröms. Profit Beyond Measure: Extraordinary Results through Attention to Work and People. New York: Free, 2000. Print.

[2] Franz, James K., and Jeffrey K. Liker. "The Toyota Way: Helping Other Help Themselves." www.sme.org. November 2012. Accessed September 9, 2013. http://www.sme.org/MEMagazine/Article.aspx?id=69059&taxid=1415.

[3] Franz and Liker, ibid

[4] Thomas and Bröms, ibid