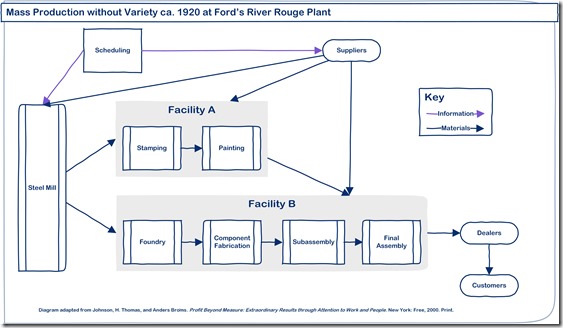

In the 1920s (almost 100 years ago), Henry Ford devised a manufacturing system that outperformed every other manufacturing operation of its day. Ford’s plant at River Rouge (near Dearborn, Michigan), along with another plant in Detroit, produced about 15 million Model T automobiles by 1927.

Amazingly, in 1925, the River Rouge plant produced about one Model T per minute with a total lead time—from steel-making to finished automobile—of about three days and nine hours (33 hours). [1]

Granted, Ford was building only one model in only one color, but still this was quite amazing for its day.

Two different views of River Rouge Supply Chain

In 1929, Kiichiro Toyoda made the family’s first pilgrimage to Ford’s River Rouge plant to learn how to make automobiles. Twenty-one years later, Kiichiro’s nephew, Eiji Toyoda, made a second three-month visit to River Rouge. At that time, Toyota Motor Company had produce a total of about 2,700 automobiles. By comparison, River Rouge was producing about 7,000 vehicles a day.

What Kiichiro and Eiji Toyoda saw at River Rouge would drive their thought-processes as they labored to build what was to become the largest and most profitable automobile manufacturer in the world over the coming five decades.

In the meantime, Ford Motor Company and the rest of the U.S. auto industry would take a different approach to manufacturing and supply chain management and find themselves increasingly unable to compete or be profitable.

Toyota built its success using inherent simplicity solutions to what appeared to be complex problems. The U.S. automakers, on the other hand, invested millions of dollars to build “data factories” alongside and within the facilities that manufactured the automobiles and components.

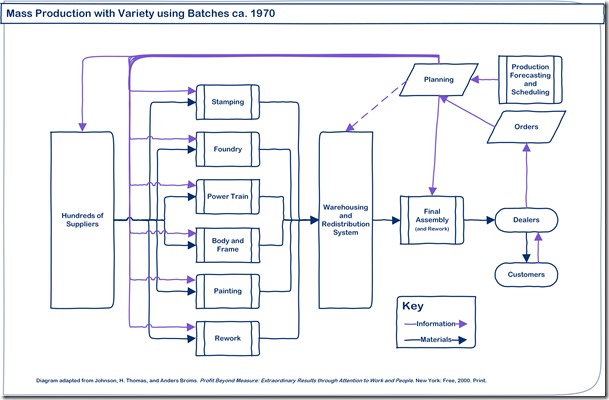

By the late 1970s, the simplicity and success of Ford’s River Rouge manufacturing concept had been turned into something like this:

Entrapped by Cost-world Thinking

While Eiji Toyoda put all his resources to work seeking ways to reduce change-over times as variety increased in consumer demand, U.S. automakers were caught in cost-world thinking and sought only to minimize total accumulated change-over time. To do this, they increased batch sizes.

While River Rouge’s success had been driven by Henry Ford’s “assembly line” or one-piece flow, managers and executives at U.S. automakers decided that manufacturing by batch and reducing the number of setups required was the way to save money and make manufacturing with variety efficient.

However, because arbitrary or calculated batch sizes are never in sync with actual market demand, U.S. carmakers opted for complex solutions in their attempts to keep actual production from getting too far out of line with actual demand.

They decided that they must spend time, energy and money on forecasting systems (to try to project demand into the future) and even more time, energy and money on advertising and sales promotion to try to keep actual demand in balance with actual production.

The result was that any savings that may have accrued in the real factory from reduced setups through batching of production was quickly swallowed up—and then some—by the expenses heaped upon the organization for advertising, marketing, schedulers, controllers, expediters, software, hardware, networks and an ever-growing IT staff.

The expenses of running the “data factory” consumed all of the savings earned in the real factory.

Instead of finding themselves more profitable for having chosen “cost-savings” in the real factory, they found themselves increasingly falling behind in profits and profitability.

The effectiveness of “flow”

What has become known as “The Toyota Way” is built upon the foundation of leveled production (Heijunka) and Toyota has put its efforts into removing every roadblock to leveled production—especially in reducing changeover times so that tremendous variety can be supported without loss in production.

Toyota’s relentless pursuit of waste and its elimination—“waste” being defined as any part of the effort that does not add value from the customers’ perspective—has led to its ability to dramatically slash waste in changeovers. Over several decades, Toyota has been able to cut away at changeover times, reducing many to less than 20 percent of the original changeover times. Some changeovers have been even more drastically reduced. That that formerly took more than a full shift have been reduced to a matter of minutes.

In short, Toyota does not rely upon—nor bear the heavy overhead—of the parallel “data factory” to manage their manufacturing operations. Virtually everything that the factory floor needs to know is encoded in the work and work practices themselves.

And, to the finance and accounting departments at Toyota, the factory floor is “a black box.” Finance does not set quantitative goals for the factory and production is not measured for “efficiency.”

Yet, the proof is in the profits.

Market capitalization for Toyota has consistently been equal to or greater than that of the sum of the Big Three automakers in the U.S. for most of the last 35 years.

This certainly shows the value of emphasizing “flow” over attempts to artificially affect “costs” in a “numbers game” run by the cost-accounting department.

And, as for “the data factory” and its tremendous overhead, I’m beginning to wonder if “Big Data” isn’t just a further excursion down the same costly road.

What do you think?

-------------------------------------------------

[1] Johnson, H. Thomas, and Anders Bröms. Profit Beyond Measure: Extraordinary Results through Attention to Work and People. New York: Free, 2000. Print.